Two days ago I went to the Gallery for a bit of archive research. But instead of Mary’s letters I thought I’d look at some institutional stuff. Down in the basement office, tucked around a corner, there is an old index card filing cabinet. I don’t suppose anyone ever notices it, it is so redundant. Nearby there is a gathering of desks and other office furniture marked for disposal. One day I shall walk into the office and find the cabinet gone. I do hope not. Despite the fact that typed index cards have been replaced by the all-encompassing micromanagement of the relational database, there is material here that resists the omnipotence of the digital.

I know these cards well, they were my bread and butter when I first got involved in the Herculean task of digitizing the collections, twenty years ago. And I had a half-remembered notion in my head that there was unique information here, the trace of past approaches to the categorising of things, something I had not noticed elsewhere in the record. So I started to go through the cards. It may be corny, but it really did feel like seeing old friends, a little glimpse back to old times and my first excitement at working in a real, live, proper art gallery. I even said a quiet hello as I opened the drawer.

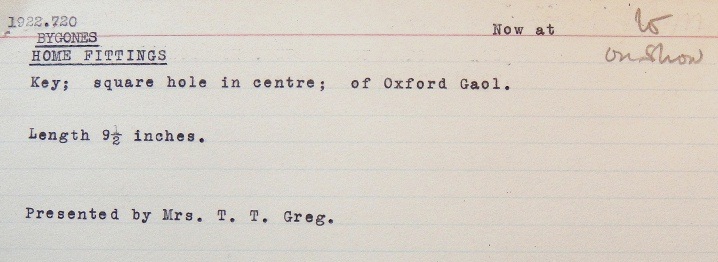

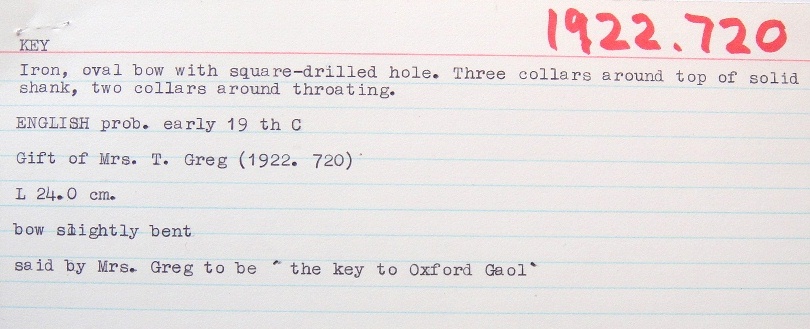

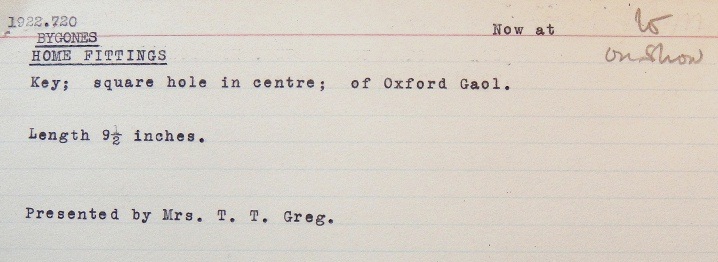

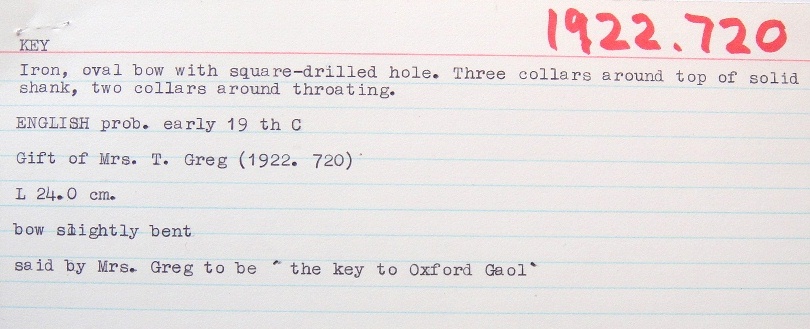

Each item in the collection has two index cards. The first, a dirty soot-grey with dense black type; the second more pristine, with bold handwritten numbers in red permanent marker and sharper type, possibly made by an electric typewriter? When do these two cards date from? Why was a second card written up, incorporating information from the first, but the first not discarded? Both are now rendered obsolete by the digital record, but still they remain. For now at least. Sometimes it’s better to go unnoticed.

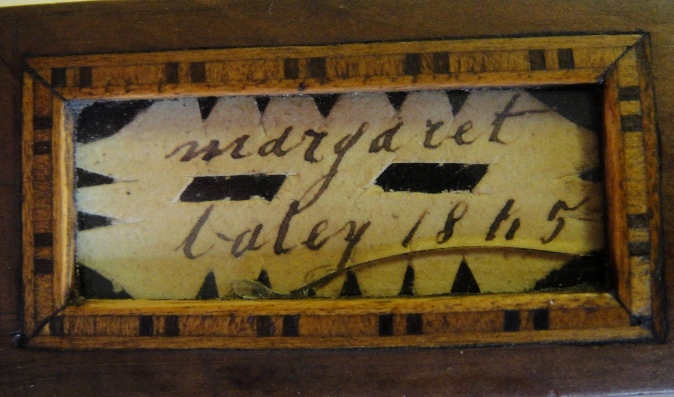

What interested me was how much could be deduced and speculated upon by considering these two different records. Incidentally, I didn’t set out knowing I was interested in this, it just occurred to me as I was looking through and re-acquainting myself with familiar things, examined with the benefit of time and distance from my first encounter with them. I found myself considering them as artefacts in themselves, rather than simply as holders of information to be transcribed.

Immediate impressions:

- How dirty the earlier cards are (from the days of smoky fires and air pollution?) and how they have a hole punched at the bottom in the centre, so they could be threaded onto a rod within the drawer, thus preventing removal and loss. I remember the index cards at the Central Reference Library used to be held by a device like this, again before the days of digital catalogues.

- How curious it is that both remain. The second card deals with and builds on the information in the first (or on occasion discredits it) but still the first was considered significant enough to be stapled to the back of the second, for reference. This takes up twice as much space in the drawer.

- The difference in type from one card to the other, from soft, dense, slightly fuzzy black, to crisp, efficient, delineated black.

- Other markings – in pencil on the earlier card (temporary, subject to change) and heavy red marker pen (dominant, permanent) on the later one. Both in the top right corner.

- The different prioritisation and layout of information on each card, what is left out and what is included, how it is written, the changes to headings, sentence structure and language.

- The way typewriters don’t obey printed lines. Sentences float in the air, intersected by lines in the wrong places. There is a tension between the instruction of the printed card (write here please) and the self-determination of the machine (no, I will set my own line spacing, thankyou). Both cards exhibit this.

I have just been reading the introduction to Museum Materialities by Sandra Dudley. Susan Pearce, who has written so much on museums and collecting, likens the evolving study of materiality and museums to stages in a human lifetime, and this seems particularly pertinent to the evidence given by these two cards. She contrasts its ‘long, peaceful childhood with clear boundaries, rules and mealtimes, which allowed for the steady accumulation of understanding that was simple as it arrived’ with ‘a turbulent adolescence with dramas and departures in which complexities emerged and innocence was abandoned’.

The first of these cards is simple, to the point: ‘Key; square hole in centre; of Oxford Gaol.‘ Object; main identifying feature; source. No uncertainties, no questioning, it is what it is, for the purpose of the record. It is neatly fitted into the category ‘home fittings’, which comes first in the hierarchy of information, in capital letters and underlined. A place for everything and everything in its place.

The second card is rather different. There is no category heading and the dominant, shouty even, information here is the accession number, big and red. This object is predominantly its number. The description is scientific in tone, ‘Iron, oval bow with square-drilled hole. Three collars around top of solid shank, two collars around throating’. I recognise this approach, the way we are taught to describe things for the catalogue. The language is mildly technical (bow, shank) although part of me is brought up sharp by the way it ends with the word throating. Two collars around throating. In years gone by I would barely have noticed this, but today it strikes me as such a bodily thing, suggesting imprisonment or enslavement, a choking restriction. How appropriate for a key.

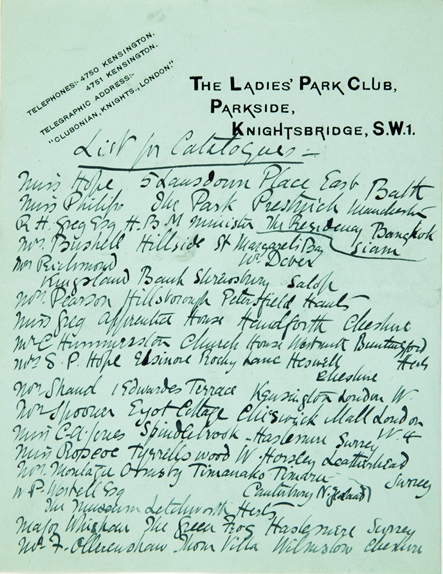

There is a loose and tentative attempt at attribution: ‘ENGLISH prob. early 19 th C‘, a new addition to the sum of knowledge, which was not given on the earlier card. And right at the bottom, at the lowest point in the information hierarchy, previous attribution is rubbished. What was previously given not only as fact, but arguably as the defining characteristic of this object, its story, has now been relegated to unreliable anecdote: ‘said by Mrs. Greg to be ‘the key to Oxford Gaol’. This is done not only by the implicit question mark within the phrase ‘said by’, but also by the use of inverted commas. In its defence, I can imagine past curators explaining the use of inverted commas as an objective approach, ensuring the preservation of Mrs Greg’s exact words. Although actually, these are not the exact words on the earlier card. Perhaps, though, I am influenced in my reading of this punctuation by the contemporary conversational habit of ironic speechmarks, two pairs of fingers wagging in the air to suggest a distancing of the speaker from what they are saying.

There is also, of course, the change from imperial to metric measurement. ‘Length 9 1/2 inches’ has become ‘L 24.0 cm.’ How exact! I could overindulge myself here, getting really stuck into the tiny detail and possibly romanticising it. 9 1/2 inches has a fuzzy quality that reflects the softness of the ink on the card; the use of full words, length, inches, and the approximate nature of the measurement itself. L 24.0 cm, on the other hand, is clipped, accurate, abbreviated.

The later card also includes a brief condition check of the object, missing on the earlier. This makes me smile briefly, as there is a mistake on the card! Whoever typed this up accidentally typed ‘o’ rather than ‘l’ in the word ‘slightly’ and had to go back over it. O is immediately above L on the QWERTY keyboard, an easy mistake to make as a touch-typist would use the same finger for both keys, but one which must have caused a cross moment. Wouldn’t happen now, all mistakes are cleaned up by the magic of the word processor. But I digress. Is there anything to be deduced from the addition of ‘bow slightly bent’ on the later card? Again, I’m slightly anxious of the potential to over-interpret. But what the hell, here goes.

I notice that the earlier card includes information of a temporary, extrinsic nature to the object, information which pertains more to the institution than the thing: the category into which this thing has been put (home fittings) and its current location written in pencil in the top right, not all of which I can decipher (Now at: ? on show). Looking closely at the pencil marks, I can see the traces of an earlier location, rubbed out and replaced with this. On the back of the card, there is the typewritten inscription ‘Transferred to Fletcher Moss Museum 24th February 1939′. Does this contradict the ‘on show’ location given on the front? I suspect it does, but I will have to check. Did the system of location management via catalogue cards fall down at some point, leaving this final location frozen in time?

By contrast, the later card deals exclusively in information intrinsic to the object and its known history. No location or movement history, no interpretive headings or categories, the reluctant inclusion of Mrs Greg’s previous attribution presumably legitimised as pertaining to its collecting rather than use history. All the information on this card seems to me to be about fixing the object, pinning it down. In this context, the inclusion of its condition, ‘bow slightly bent’ would seem to be an attempt to freeze its physical state. It is not a perfect, mint-condition object, but we can differentiate between historic damage (intrinsic to the history of the object and therefore legitimate) and the potential for further deterioration which must be prevented.

Having just read this through and then glancing back at the pictures of the cards, something else occurs to me, which I do not think I would have noticed if I hadn’t already written this. The difference in how the acquisition of this object is described on each card.

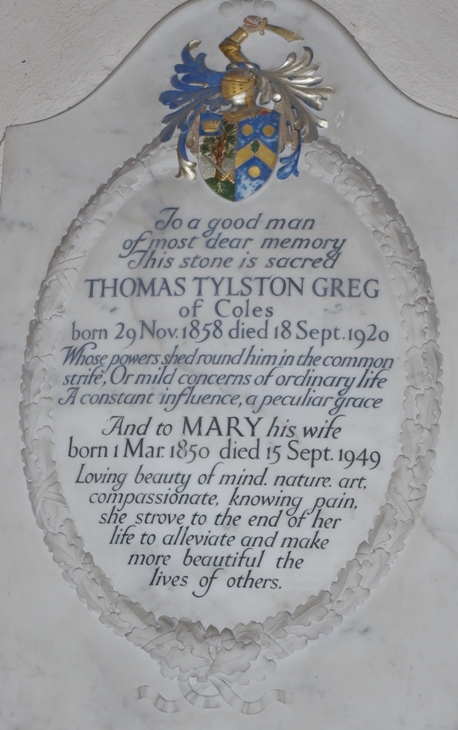

Earlier card: ‘Presented by Mrs. T. T. Greg.’

Later card: ‘Gift of Mrs T. Greg (1922.720)’

Verb versus noun. The earlier card describes an act of donation by an individual. The later card reframes this as part of the nature of the object. The act is gone, the object remains. And is reinforced by the bracketed repetition of the accession number. As if we needed reminding! Does this card suggest a subconscious anxiety about the nature of this object? The earlier card certainly seems more relaxed!

So much to be considered, from two apparently straightforward documents. And I haven’t gone into other things I notice. The later card is flimsier than the earlier one and is correspondingly dog-eared along one edge. The later card is inconsistent in its approach to punctuation and grammar; descriptive sentences with capital letters and full stops (but no verbs) at the start, capitalisation of ‘Gift’ further down but no full stop, then just free-floating phrases, no punctuation at all (apart from the MG quote) at the bottom.Tippex! I’ve just noticed it, on the later card. The ‘i’ of ‘drilled’ in the first sentence has been retyped over Tippex. And yet, the typo below has been left. Oh dear, this way madness lies.

Some questions that arise from all of this. Firstly, how can I work out when the second card was produced? I notice that other cards have book references on them, the latest of which (so far) seems to be a publication from 1974, so they must have been produced sometime between 1974 and 1993 when I first started work. I can probably narrow this down. Secondly, why were new cards written at all? It must have been a considerable, time-consuming task. Contrary to my received knowledge (that the MG collection was pretty much forgotten after 1949) it suggests an attempt to re-value the collection, to bring it into the modern museum world. The cards reveal quite a bit of research – new descriptions, condition assessments, attempts at a more scientific attribution and bibliographic referencing. Was this project specific to the MG collection or did it take place across the entire Gallery? My memory suggests it did actually; I think there are new cards across other areas as well, but I need to check. If so, what prompted such an ambitious exercise?

And the big one, of course, is what does this contribute to our understanding: of the collection, of the institution, of the wider world and our relationship with stuff? Honestly, I don’t yet know. But what it does do is add colour and texture to the picture that is forming in my mind, suggest avenues of research I might follow up, chime with some of the things I am reading (be wary here though, not to just pick and choose what fits nicely) and provide me with the opportunity to practice looking, thinking, writing, thinking, looking some more, etc. etc.

Back to the Gallery tomorrow, to continue my original task, which was the collecting of categories – the Home Fittings and other typologies given by the earlier cards, which don’t seem to appear elsewhere. But whilst doing this, I shall also be thinking about my observations to date and where they might take me.

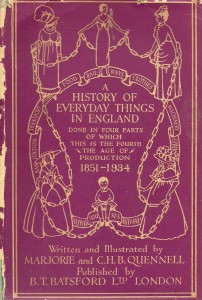

My PhD thesis is entitled ‘Everyday life’ and ‘everyday things’ in British popular culture, c.1910-1969. It examines how people published, preserved, and sometimes sought to re-make, the ‘everyday’ past in British popular culture. One chapter focuses on the life and work of Charles (1872-1935) and Marjorie Quennell (1883-1972), in particular their series A history of everyday things in England (1918-1934), and its reception. As ‘amateur’ historians in an age of professionalization, the Quennells enjoyed much commercial success with these books. They showcased social and aesthetic history instead of the more familiar political epochs. When Charles died in 1935, Marjorie became the first female curator of the London County Council’s newly overhauled Geffrye Museum in Shoreditch.

My PhD thesis is entitled ‘Everyday life’ and ‘everyday things’ in British popular culture, c.1910-1969. It examines how people published, preserved, and sometimes sought to re-make, the ‘everyday’ past in British popular culture. One chapter focuses on the life and work of Charles (1872-1935) and Marjorie Quennell (1883-1972), in particular their series A history of everyday things in England (1918-1934), and its reception. As ‘amateur’ historians in an age of professionalization, the Quennells enjoyed much commercial success with these books. They showcased social and aesthetic history instead of the more familiar political epochs. When Charles died in 1935, Marjorie became the first female curator of the London County Council’s newly overhauled Geffrye Museum in Shoreditch.

Comments