In response to Hazel’s beautiful to do lists.

Lists are everywhere. I have found myself increasingly fascinated by the list, partly because of Mary’s rather peculiar inclusions on her lists (hence the title of this post) and because in order to keep myself on the straight and narrow in my brave new world of PhD-dom, I am constantly writing them. Now I see lists everywhere, it is a form that is universally used. There are different kinds of lists, each with its own narrative quality; the mundane and everyday – shopping list, packing list, ‘to do’ list; the exclusive/inclusive – A-list, guestlist, blacklist, hitlist; the structuring and creating of order – playlist, tracklist; the competitive – longlist, shortlist. And Hazel’s ‘to do’ lists just show that even the apparently ordinary can be precious. There is the roll call, from the school register to the list of names on a cenotaph. How can such a raw and bald form of words have such poignancy?

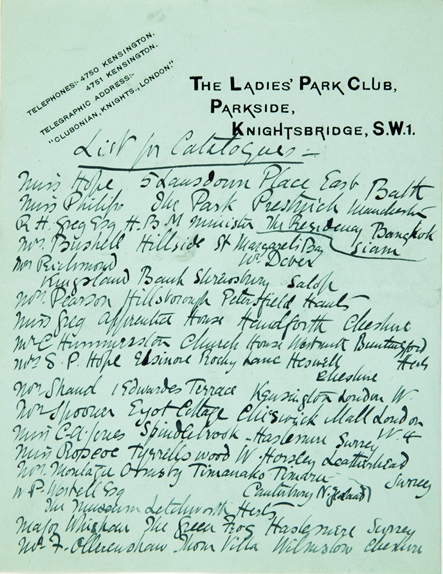

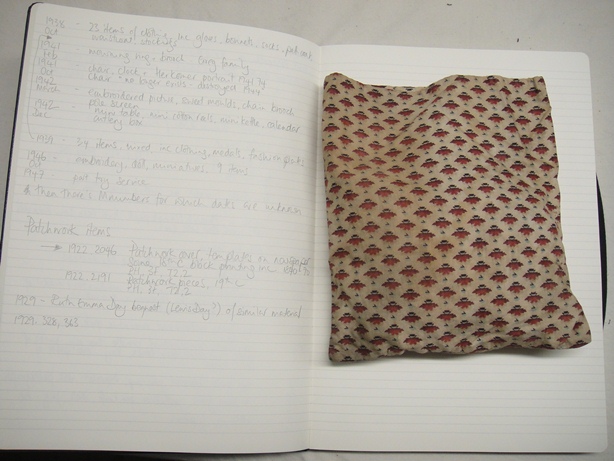

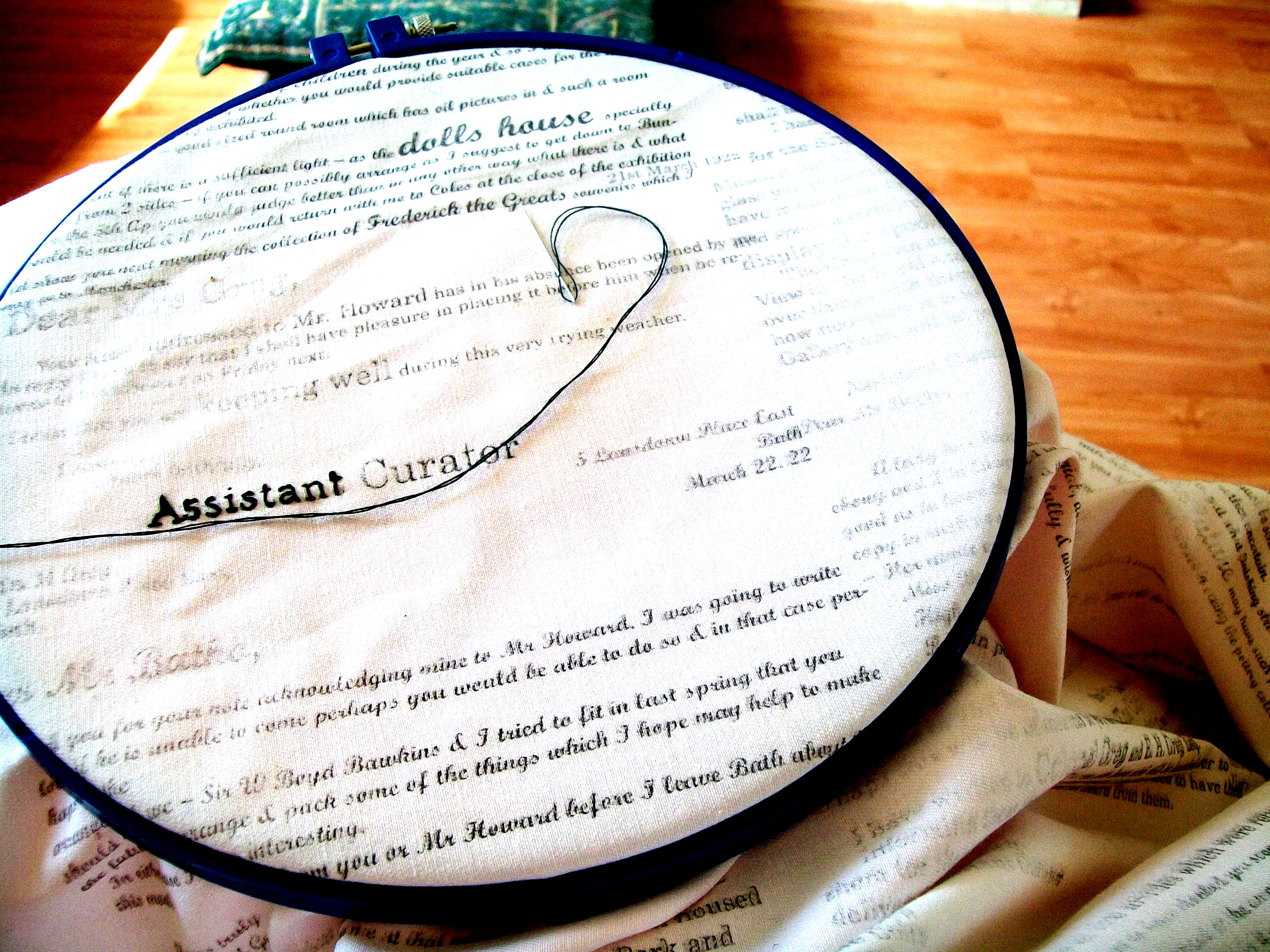

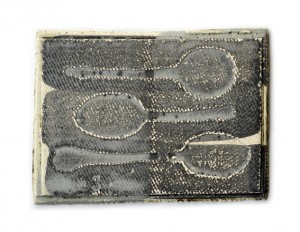

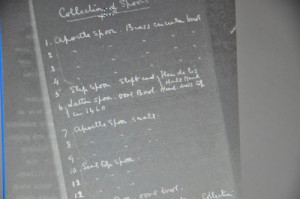

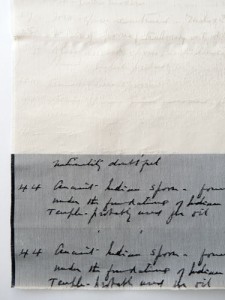

At the core of every museum in the world is a ‘superlist’ – the accessions register. Kept under lock and key down in the depths of the basement, it is the heart of the institution, holding within itself the museum’s past, present and future, not just in the items it describes, but in the descriptive language used for each new acquisition; in the changing conventions of date, name, title (who uses ‘Esq’ any more); in the handwriting, from the inked copperplate of the earliest pages to the more idiosyncratic black biro entries of more recent times. And it is never complete. More on this shortly.

People understand the concept of a list, it is deceptively transparent, even objective; the reduction of thought/information/knowledge to its barest bones. Guidelines for writing for the web often advocate the use of bullet points rather than paragraphs – easier to read and a more efficient way of transmitting information quickly. A comment from Tom; lists are a product of fear – fear of loss, fear of forgetting, fear of distraction and disorder, fear of incompletion. To list is to control the material you are listing, to set parameters around it and to put it in order. It is a very explicit statement of control, there’s nowhere to hide in a list. Another comment from Tom; this is why politicians don’t like them. It’s much easier to obfuscate and hide woolly language and empty promises in a conversational format of words. Back to the writing for the web guidelines.

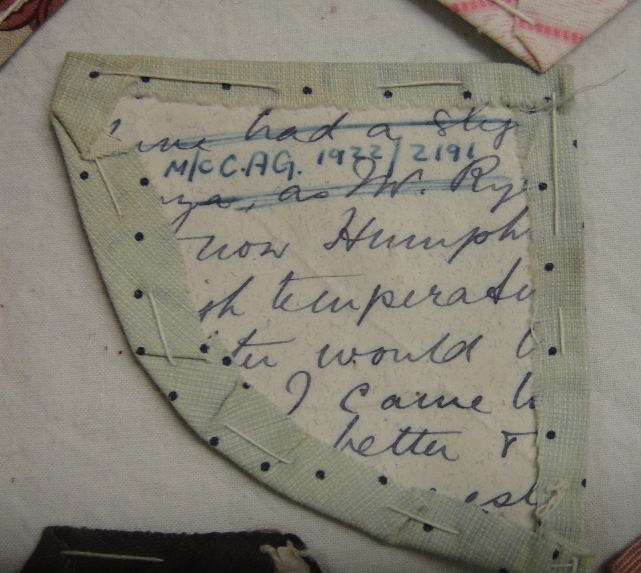

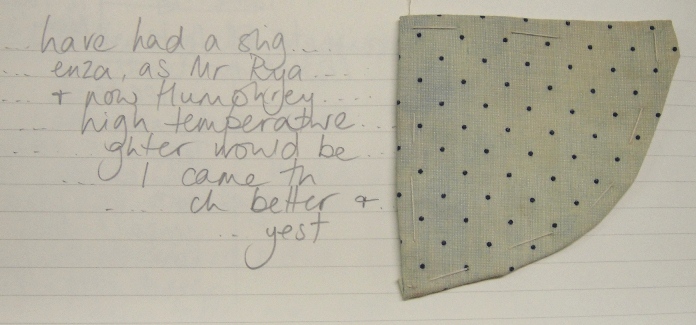

And yet. If a list is made of explicitly constituent parts, there is a clear path to dismantling it. It’s like lego, just take it all apart and rebuild it into something else. And when you do that, your list says something rather different, which suggests it’s not such a transparent format after all. There is fun and subversion to be had from taking a list apart and rebuilding it differently – Tom Lehrer reworked the order of the Periodic Table to form his brilliant song The Elements, set to Gilbert and Sullivan. My son’s Year 5 primary school teacher used to mix up the alphabetical order of the class register from time to time, as he had noticed that the children often answered before their names had actually been called and he wanted to wake them up a bit. Disrupting a list is provocative. This relates to a thought I keep coming back to about value and meaning in the collection and my current pre-occupation with inscribed objects. What if I were to re-catalogue the collection according to all the names that have been written on it? What kind of a collection would it be then? More like the cenotaph perhaps. The list could be read as the ingredients (ooh, there we go, that’s another one – the instructive list), setting up the reader to imagine the story in the spaces between the entries.

This came up in conversation with my Mum yesterday. She writes, but was rather sceptical of my new-found fascination. And yet, soon found herself telling me about the day she sat in a cafe and decided to write 500 words about the menu, without actually mentioning anything on the menu. She wrote the story of the list, hidden in between the sequenced elements, flipping the whole thing round so the story emerged as the list disappeared.

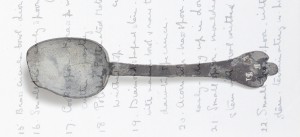

So, although the concept of the list suggests containment, control and completion, it actually has infinite possibility. I discovered the other day that there is a book by Umberto Eco, called The Infinity of Lists (haven’t got hold of it yet, but it’s on my Christmas list). Found myself thinking of the list more as a runaway train, accelerating and decelerating under its own momentum until it finally runs out of steam. The empty pages of the accessions register will go on forever, as long as the museum lives. There is something of this quality in Mary’s collection and the lists that go with it; a sense of uncontrolled proliferation. This I think has something to do with the sheer size of it – in marked contrast to the smallness of the individual things themselves; the simple heartbeat of repetition – page after page of ‘key, 19th century’, ‘key, 19th century’; and the unexpected juxtaposition of the supposedly ordinary and the bizarre – ‘the fossilised eye of a fish’.

Liz

Comments