An ordinary day dress

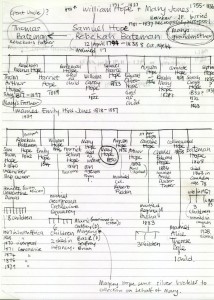

A couple of weeks ago, I gave a paper at the conference How Do We Study Objects? organised by Artefacta, the Finnish Network for Artefact Analysis, in Helsinki. It was lovely to be talking about Mary to an interested audience of international academics including historians, curators, archaeologists, anthropologists, artists and designers, all of them investigating the myriad ways and means by which human beings relate to the material world. There is a real groundswell of interest in Mary that continues to grow, evidenced by several new projects emerging from the individual interests of the original MMQC team and some exciting conversations that have recently taken place. But more of that to come (hopefully).

My Helsinki paper focused on a dress in the stores at Platt Hall, which I first looked at a few months ago as part of my attempt to audit the entire collection, a rather overwhelming task, spread out as it is across three sites. The dress in question is an ordinary late 19th century day dress; bodice and skirt in mushroom-coloured shot silk, with lace collar and cuffs. The typically brief entry on the catalogue card identifies it as a wedding dress c.1896, although Miles (Curator of Costume at Platt) tells me there is nothing intrinsic to the dress to identify it as such.

My Helsinki paper focused on a dress in the stores at Platt Hall, which I first looked at a few months ago as part of my attempt to audit the entire collection, a rather overwhelming task, spread out as it is across three sites. The dress in question is an ordinary late 19th century day dress; bodice and skirt in mushroom-coloured shot silk, with lace collar and cuffs. The typically brief entry on the catalogue card identifies it as a wedding dress c.1896, although Miles (Curator of Costume at Platt) tells me there is nothing intrinsic to the dress to identify it as such.

The day I first looked at it was typical of those spent with the collection, on my own in the quiet of the museum store. I love these days, they are almost meditative – the humdrum everyday world falls away as I slip into the reverie of close encounter with the tiny detail of material things. As I am not so well versed in historic clothing (ceramics being my curatorial thing) I don’t find the dress ordinary at all, but am captivated by things both familiar and alien about it – the narrowness of the waist, the heavy fall of the pleated skirt, the hidden secret of a pocket deep within one of the pleats. The sheer number of hooks and eyes everywhere, there are seventeen down the front of the bodice alone, to hold, shape and contain the female body. It is so ‘done up’.

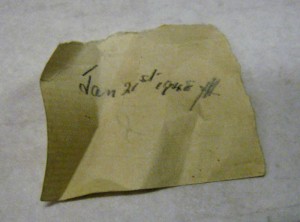

This is the nature of looking at the collection in store, the sense of wonder that it engenders. I was having a nice day. Then I happened to look inside the neck, where the lace collar is sewn into place on a white cotton tape. I got such a shock I nearly dropped the whole thing. A name was written in the bottom corner of the tape. Throughout my investigation I had been idly speculating on things I knew – the dress was given by Mary Greg, the catalogue card was probably transcribed from one of the many lists supplied at the point of acquisition, the attribution (as with many other objects in the collection) probably supplied by her. Mary and Thomas Greg married in 1895. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if…

This is the nature of looking at the collection in store, the sense of wonder that it engenders. I was having a nice day. Then I happened to look inside the neck, where the lace collar is sewn into place on a white cotton tape. I got such a shock I nearly dropped the whole thing. A name was written in the bottom corner of the tape. Throughout my investigation I had been idly speculating on things I knew – the dress was given by Mary Greg, the catalogue card was probably transcribed from one of the many lists supplied at the point of acquisition, the attribution (as with many other objects in the collection) probably supplied by her. Mary and Thomas Greg married in 1895. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if…

Written on the tape inside the neck was the name M.Hope.

For a fraction of a moment the dress in the museum store-room was transformed into a real, living, breathing person in my arms. It really felt as though I was holding Mary, not a museum specimen. It was slightly scary actually, I had to put it down and take a step back. And have a think about it. Could this really be Mary’s wedding dress? Or is this wishful thinking, the over-enthusiastic imaginative leap? Does it matter? In the moment when a name inside an old dress came together with a particular set of interests and historical knowledge, it became Mary’s wedding dress. Once I’d calmed down a bit, I began to think this through. If it was indeed, Mary’s dress, how was this not known? But then, little was known (or remembered, at least) about Mary before we embarked on this project. Few beyond the MMQC team would know enough to connect the names Hope and Greg, and although there are other objects in the collection that were made by or used by Mary, she didn’t make any attempt to claim authorship or ownership of them in the historical record. According to Miles, it could well be the kind of thing an older woman (she was 45 when she married), especially one of Liberal non-conformist views, might wear on her wedding day. It is thus not unreasonable to suggest that this could be Mary Greg’s wedding dress. Until we find a picture of her wearing it, it’s not possible to say anything more certain than this. It is her dress… but it might not be. As has been observed previously by others on this blog, there’s something quite thrilling about this ‘is it or isn’t it’ status. Objects are funny like this, they resist being pinned down entirely, that’s what’s so compelling about them.

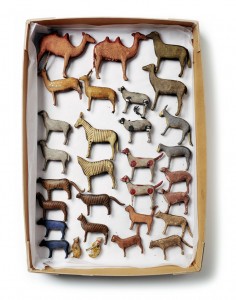

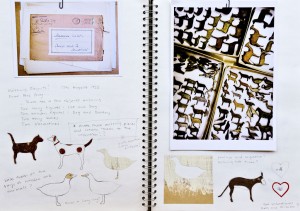

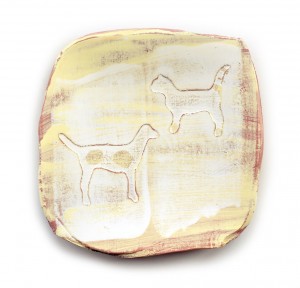

So that’s what my paper was about. Not in itself a find of international significance, but one of great poignancy and personal meaning for those of us who have come to know Mary through her letters and collections. It was as Mrs Greg that Mary Hope built up her collections and provided so many museums with a founding legacy on which they continued to build. For me, it was a powerful instance of the capacity of material things to pack an unexpected punch; to transform themselves in a moment, from one thing to something utterly other; to give up, in the smallest of details, insights that can leave you reeling. A reminder that history is not only to be found in the written pages of archives and books, but is inscribed in the very stuff itself. And that museums are full of the echoes of real lives, once lived.

Liz

Comments